wet like an open vowel sound

October 14 - November 26, 2022

by Joy Wong 黄祖欣

essay by Jody Chan

I enter, as always, into language. The gallery window opens onto Dundas and Chinatown. Rain and sun, from an indecisive mid-October morning, take turns stumbling into the panes. Behind the glass, SCOBY skins stretched thin evoke flags, curtains, laundry suspended on wooden frames. Joy shows me ceramic urns and glass jars on a blank shelf, their purpose still undetermined. My senses register the sting of vinegar, the soothe of earthen, biological tones — ochres, maroons, forest greens — suffusing the air with an ephemeral light. In this room, objects are linked, held together by tubes, netting, string. Arterial. The conversation between Joy and I collides with image and sound, foam sleeve and nylon fruit bag. In this room, I come to know, the bodies are porous. The bodies signify. The bodies hold.

[ ]

A mother is a slippery thing: she brings you into the world and then departs. All your mother has left for you are these rough-cut memories that both sting and shimmer when held too closely.

—Akil Kumarasamy, Meet Us by the Roaring Sea

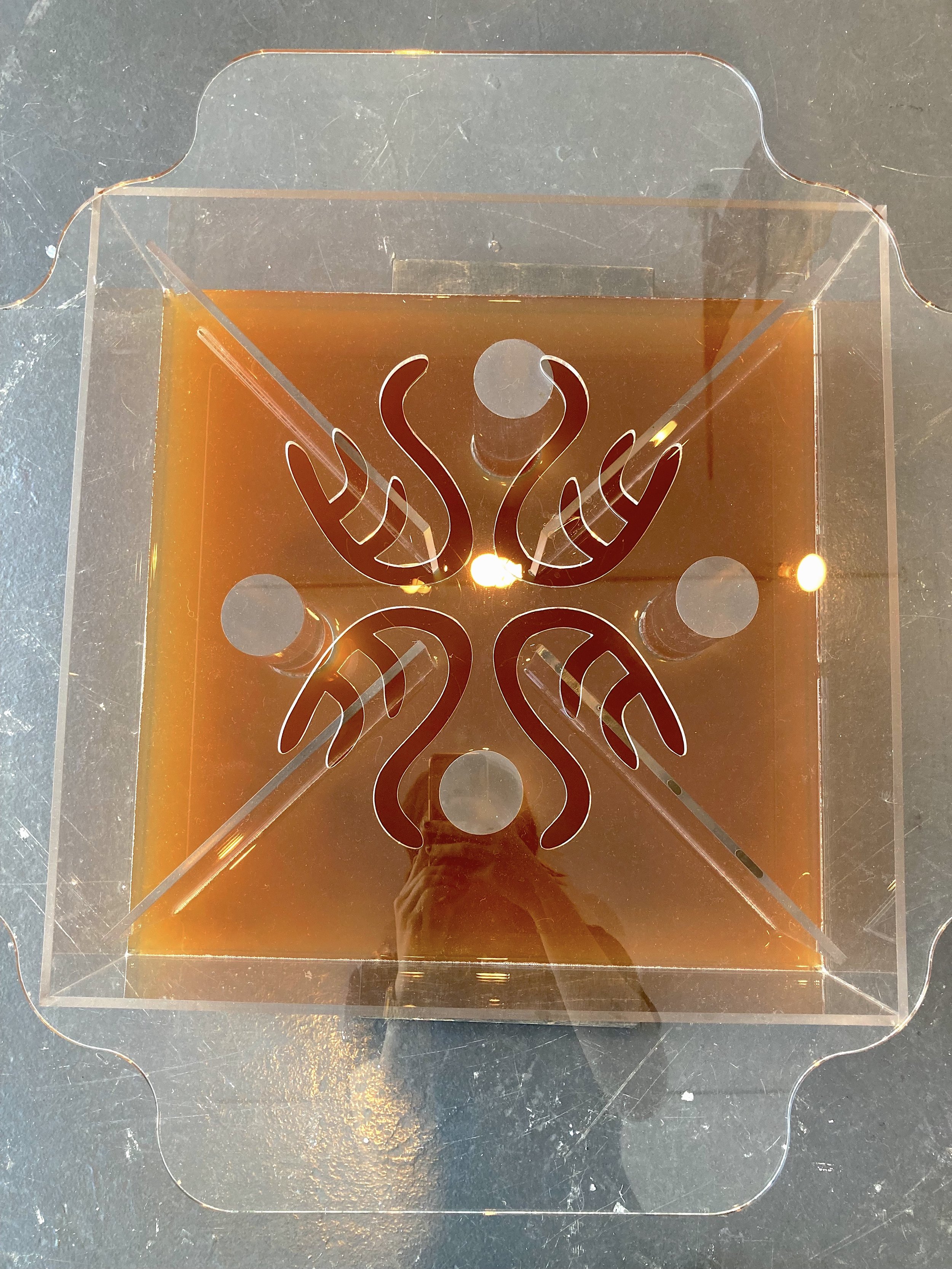

At the centre of the slate cement floor, we encounter a mother. The gelatinous film, still newly forming, swims inside a four-organed plastic vessel, inside which kombucha will ferment for the next month— the duration of the exhibition. On the plastic tub’s lid, custom-cut, four stylized calligraphic repetitions of the Chinese character for ‘meat’ (肉) combine to make up the character for ‘stomach’ (胃) — once a pictograph, an image of rice held in a mouth.

Joy’s work is an archive of transformation. Over time, exposed to air and light, the hanging skins darken. The character for ‘mother’ loses its edges, becomes a vessel for water. Language, too, is a mutable surface, a thing that stings and shimmers and slips.

[ ]

Mary-Kim Arnold suggests that language functions to hold the soul and spirit of a people, allowing people to recognize that they belong together, and compelling them to preserve their own continuity. If it’s true that language derives from the embodied experience of belonging, what we can perceive and conceive of as collectivity, what are the words that form out of fermentation? What is the language struggling, alongside litres and litres of sweetened tea, to be born? To describe the descendance of multiple generations of kombucha from a single starter?

I feel loss. I feel absence, Arnold writes. I will name this absence mother.

[ ]

Mother, mother tongue, motherland. ‘Mother’ necessarily describes displacement— from a body, a language, a lineage. Once a part of — through syntax, through flesh— then apart from. So then, what does it mean to return?

Joy tells me that the SCOBYs take on the qualities of their environment; an epigenetic collaboration, of sorts. They had to take care, for example, to keep the skins they pulled during an artist residency in high-altitude, low-humidity Banff from drying out and shattering in storage.

I can’t help but wonder: does a body remember, on a cellular level, the mother it descended from, the grammar of its growing?

[ ]

I forget, sometimes, that descendance is a sensual thing. The dampness of hands. An ecology of breath, of bodies meeting open-mouthed, their edges only softly articulated by window or lamplight. The blurry nature of both birth and death, distorting the boundaries between outsides and insides. Between the singular I and we we we we we, simply a recycling of material. Compostable, biodegradable; that is to say, alive.

[ ]

In translation between English and Mandarin, the terms of fermentation gain yet another set of significations. Mother, motherland — an abstraction repurposed by the Chinese government for nationalist, fascist aims. SCOBY: another word for mother. Or: Symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast. What is a symbiotic colony? What is a benevolent state? Mother, then: an oxymoron?

[ ]

In an interview, Miki Kashtan claims that before we encounter the world of exchange and accumulation, each of us holds a cellular memory of receiving. That mothering is the act of orienting unilaterally toward another’s needs.

And yet, descendance — as opposed to mothering, which must, in Kashtan’s definition, be an active choice— can exist in a form entirely divorced from care. I think of queer and trans people, the often inhospitable family environments we grow up in.

Can the mother be said to care for each batch of kombucha, simply because it nurtured the brew from its flesh? Can a country haunt a lineage? Can a body memory a home? Maybe this work is born out of the rupture between mother and ancestor. Maybe descendance describes not only a relation of bodies, but the desire to move against, or at least away from, one’s original root.

[ ]

The root is not important. Movement is.

—Édouard Glissant, The Poetics of Relation

Between mother and ancestor, there is no space for singularity. Generations branch across names, choices, geographies.

Sometimes, a mother is a broken promise. Sometimes, a promise is a wish.

Kombucha itself has a murky origin story. According to some, it comes from the Bohai Sea district in northeast China. Another legend claims a Korean doctor named Kombu brought the fermented tea to treat a Japanese emperor’s illness. On a map, I find the Bohai Sea neighbouring what is now Korea Bay. A sea next to a bay, bordering a landmass with lines traced over it.

[ ]

When we brew kombucha, isolating the first mother, initial batch, original culture, becomes impossible. In that way, there can be no single, totalizing — or totalitarian — root.

In the hands of the PRC government, the promotion of simplified (standardized) over traditional Chinese across regions as broad and disunified as mainland China, Malaysia, Singapore, and Hong Kong is one such totalizing gesture. Another definition of motherhood: a relation governed by asymmetries of power. To universalize, here, is to lend legitimacy to the project of domination.

I run my hands, my eyes over the translated artist statement on the wall of the gallery, created by reducing the number of strokes, unraveling each character’s body. Brushing over its history.

[ ]

Here, too, nurturance reveals itself as non-linear. The descendant brews feeding, in turn, the mother. Joy’s hands, stretching each fragile canvas to let the light in. Rubbing beeswax into the papery membranes. Shaping the dowels to hold their weight.

They admit the futility of forcing their materials to take on qualities — of pliability, of permanence — other than what they already possess. Instead, she cares for them. She allows the environment to influence how the work will change.

Caring as collaboration. Manipulation as the use of hands. The hands that wielded the laser that cut the fermentation vessel’s panels. Stomachs, rice, and meat out of a polymer sheet. Hands that flick the gallery light on and off, that adhere labels to walls, that beckon passersby through the window in a gesture of welcome.

[ ]

LOSING A LANGUAGE

I saved Mother’s words,

buried them in the ground. How

do I only kill the weeds?

— Victoria Chang, The Trees Witness Everything

In fermentation, a contaminated culture is deeply undesirable; can create unpalatable flavours and aromas, can damage all subsequent generations. General consensus: keep the culture clean.

Gardening enthusiasts offer similar advice. Left alone, they say, what we call weed can consume an entire garden, strangling the soil to grow taller and stronger each day. Picture monocultured lawn, a green devoid of bodies. Remember, then, that weeds can also attract bees, butterflies, finches, sparrows, spur the growth of a cacophony of wildflowers. We we we we we.

So what if we left a corner for the weeds? What if I wanted to hold the weeds close, dig the words up, let their spines sting my hands?

[ ]

What language do our cells remember? Perhaps the distance between memory and mother is better crossed by the senses. By blurring, leaking, brushing, dissolving, cracking, shattering, stinging, slipping. Every word becoming a promise. Every wish becoming a world.

Care as contamination. Care as continuation. A belonging that moves against nationhood. A diaspora of many-rootedness. A community of here.